- Home

- Cecilia Velástegui

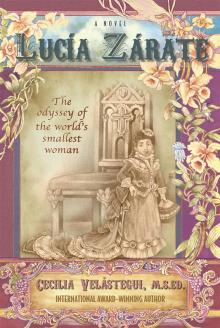

Lucía Zárate: The odyssey of the world’s smallest woman Page 5

Lucía Zárate: The odyssey of the world’s smallest woman Read online

Page 5

He guffawed. “I ain’t worrying about you, woman. It’s the little mother lode over there that I’m worried about.” He pointed to Lucía.

“Sir, everyone will get their mordida, and once their commissions are safely in their pockets, all will be well. In no time, they will all be drinking our famous coffee with milk at the Gran Café de la Parroquia and celebrating this exciting afternoon. If I may say, sir, you’re not the only one in show business. The turbulent display you’ve just endured is just a Veracruz-style business negotiation— although, in all honesty, sometimes foreigners do end up missing.”

The Yankee agent did not shake hands with the spineless notary who had extended a limp hand. Instead he patted his hidden holster with menace.

“Just you be on the boat with Lucía,” he said sternly. “Don’t get yourself killed on the way home from this hellhole.”

“You’re too kind to worry about my well-being,” she replied. “But don’t worry. When you leave this office, you will see a brawny, coconut vendor with a very sharp machete, right outside the door. He’s ready to escort me home.”

“You’re my kind of woman, Zoila” the Yankee said, turning to wave to the greedy group, all staring at him. “Adios, pirates!”

As Zoila predicted, once their pockets clanked with the Yankee’s bounty the four so-called pirates were ready to slink back into the stormy atmosphere of Veracruz and ponder their own mucky gluttony. Each one walked toward the café somewhat satiated, though not quite enough to feel completely satisfied. Their cloudy thoughts in no way reflected any concern over Lucía and her upcoming journey to a far-away place. Whatever was preordained to happen to her would take place far away from Veracruz and wouldn’t impact their lives whatsoever. The only thing that annoyed them is that others would profit from Lucía. In fact, the only thing her tiny, flawless presence had done for the pirates was to amplify their sense of their own insignificant lives, and to leave them with an appetite for more exciting experiences.

The pirates had to acknowledge that the diminutive and exceptional Lucía was on her way to finding the streets paved in gold in the United States, while they were left green with envy at her good fortune. They were all so self-absorbed, they didn’t ponder the way Lucía’s size limited and defined her daily life, nor on the obstacles she might face once abroad. They didn’t care if she needed help to walk down stairs or climb into horse drawn carriages, or to make her way onto a streetcar, in the crowded cities of the United States. They didn’t realize that the simplest task, such as washing her hands, meant Lucía had to ask for a step stool.

More telling, they didn’t notice that while their ranting against the Yankee heightened in the notary’s bureau, Lucía had lost her usual sunny disposition and cowered inside the market basket. The more they talked about her, as if she weren’t present, Lucía rolled up like a cold alley cat and tried to cover her ears with her fists, hoping to find warmth and solace in her own waning flame. No one had even glanced her way.

All they knew was that, in a matter of forty-eight hours, Lucía was boarding a ship heading for New Orleans, New York and places beyond. They, on the other hand, had to trudge wet and unfulfilled to the Gran Café de la Parroquia feeling duped by both the Yankee agent and Zoila. It was as if they had been invited to an opulent banquet and had only been permitted to sniff the gourmet food, leaving with just a single drumstick and one measly half of a sugary buñuelo. Without uttering a single word, their collective greed became the sandy irritant that soon formed into a warped pearl. Each one looked around the others, seeing the same anger in their eyes. Within hours they would all show up at the dock, form a pirate squadron, and carp at the Yankee until he shelled out a bonus mordida just to be rid of them.

Zoila, Señora Zárate and her exhausted children were the last to leave the notary’s office. All the people who’d been crowding the office, including her husband and Rosita, hurried away to be swallowed up by the rain and fog. Señora Zárate sensed their lingering greed among the moldy books and dusty documents. She squinted through the cracked, hazy window and only caught a brief shadow of the coquero while he sharpened his machete. The glimmering blade gave her solace. Perhaps her little Lucía would be safe under the Zoila’s shrewd supervision.

Señora Zárate rounded up her children, carrying one away on her back and clutching at the others’ hands. Lucía’s care she left to the new governess. The Señora gave a sigh of relief. Perhaps this one child, the runt of her litter, would feed her entire family, just by being her unique self.

“Zoila,” Señora Zárate begged, “please let’s leave this nightmare of an office. The miasma in this room is choking me.”.

Zoila had no patience for Señora Zárate’s theatrics. She was concerned more with practical, if felonious, thoughts. Thoughts that her father would have acted upon immediately.

“Yes, we should leave right away,” Zoila said, trying to appease Señora Zárate. “We need to prepare for Lucía’s voyage. Gather all your items, and I’ll look at the documents the notary prepared.”

Before she left the office, Zoila reviewed the sloppy paperwork that the notary had carelessly left out on top of his desk. He’d assumed that everyone was as eager as he was to make tracks from the office, and he’d seen no need to safeguard the documents. All he wanted was to beat the others to the café so he could get first dibs on bragging rights for outfoxing a Yankee. Unfortunately, he walked too slowly, and soon Señor Zárate, the Mexican agent, and Rosita caught up with him, all sloshing in their wet shoes along the oceanfront toward the café.

Zoila selected two significant documents outlining Lucía’s travel schedule, and grabbed what looked like an authentic United States certificate of residency. In one pile she found a suspicious-looking birth certificate from Louisiana with Lucía’s name on it, along with a contract for Lucía’s future earnings. If the Yankee agent was right about traveling to Europe as well, they would need official documents to prove that Zoila was responsible for Lucía. This jumble of stained records would have to suffice.

Zoila hesitated before she picked up two sheets of the notary’s blank paper, and then pressed the notary’s embossed seal at the bottom of each page. As her father’s daughter, she inherently knew that at some future date these would be useful. Once she was in the United States, and worked out what the Yankee was planning, Zoila could figure out how to complete and use each sheet of paper to her advantage.

She knew that the first port of call on their voyage was New Orleans. Louisiana still used a form of the French legal system in which notaries had powers similar to attorneys, so these blank documents could be very useful to Zoila. She rolled all the documents and tucked them into a narrow cylinder. This she wrapped in her linen handkerchief. The final step, for added security, was slipping the tube safely between her breasts.

Lucía lounged in the market basket, watching Zoila hiding the documents.

“Are you burying more secrets in your bosom, Zoila?” she asked, with a tinkly laugh. Zoila raised her finger to her lips and winked.

Lucía brightened up. Her jet-black eyes sparkled in the candlelight, her puckered lips as sweet as fresh-picked cherries. Lucía loved playing games, so she winked back at Zoila. But she wasn’t content to stay quiet. “Will the papers smell of vanilla, too?”

Zoila nodded.

“Are you going to write a love letter on the blank paper? Is your beloved going to write a letter back?” Lucía paused, but only long enough to think of more questions. “Will you read me his letter? Will you teach me how to read?”

Zoila was relieved that Lucía’s questions were more about romance than forgery.

“I will teach you how to read and write,” she promised, “and how to speak English so you can charm your audiences.”

Lucía smiled. “Teachers open doors,” she said. “Isn’t that right?”

Dusk had descended on the street, drawing ominous shadows between the buildings. Zoila wanted to prevent any prying eyes from

falling on Lucía, so she carried her through town in the durable market basket, covered with a shawl. She followed Señora Zárate and the children at a short distance, but stayed close to her bodyguard. The coquero, with machete extended and ready to strike, seemed to relish his new role as a chivalrous knight: he escorted the women and children, with exaggerated caution, to the home of an aunt of the Zárate clan a few blocks away.

Within minutes of meeting the three adult relatives, Zoila knew she didn’t trust any of them. Señor Zárate’s gray-haired aunt asked crass questions about the amount of money given for sending Lucía abroad. There was no real affection there, that was clear, from the old aunt or her two adult daughters. They stood sucking their fingers, still tacky with hot sauce, and ignored the cranky and hungry Zárate children.

That night, rather than returning to her godmother’s home, Zoila slept on the floor alongside Lucía and her siblings. She rose at dawn the following day, and asked Señora Zárate to give her Lucía’s baptismal record. Zoila knew that the bogus Louisiana birth certificate she’d hidden would not fool an alert immigration officer in New Orleans.

Señora Zárate hemmed and hawed. “I don’t think we have the baptismal records here,” she said, obviously lying.

“I’ll get them from the parish priest,” Zoila said, determined to call her bluff.

“Lucía wasn’t baptized in Veracruz,” Señora Zárate countered. “But don’t worry. The Yankee will have no trouble getting Lucía the correct travel documents.”

Zoila drew herself up like the persnickety governess she was pretending to be.

“Señora Zárate,” she said, in her take-charge voice. “I attended the Sacred Heart boarding school in Louisiana for two years. Believe me, I know what documents will be needed upon arrival in New Orleans. Now, where can I obtain Lucía’s baptismal record?”

“You don’t understand,” wailed Señora Zárate, her face distraught. “We … we baptized the children in different churches, you see! Some we didn’t even have the time to baptize, and now my poor angels will never be able to meet me in heaven.”

She began to sob and, on cue, all the Zárate children started to cry along with their mother: this brought the three alarmed relatives rushing into the tiny bedroom. They couldn’t make sense of what was upsetting Señora Zárate. All they heard was Lucía’s name, so they assumed the worst of her.

“I think the priest didn’t want to baptize Lucía,” one sister whispered to the other, “because she might be a chaneque.”

The women shook their heads in disgust at having a chaneque in their midst.

“It’s not right to allow Lucía to stay here in this house,” said the other sister, pouting at the old aunt. “She might steal our children’s souls. That’s what chaneques do, you know.”

Rather than have the relatives stay there, further agitating Señora Zárate with their mention of the word chaneque, Zoila took charge again.

“As you can all see,” she said, “Señora Zárate is very emotional right now. She’s very happy about Lucía’s wonderful future, but like any mother she’s sad as well. Aren’t you, Señora?”

“I’m only sad,” cried Señora Zárate, and Zoila realized that she needed to direct the conversation a different way before Lucía’s mother fell apart. She gave the three relatives her sternest look.

“I have assured Señora Zárate that I will take good care of Lucía while she travels all over the world.” Zoila puffed herself up to her full width and height. “I’ve lived in the United States and no Yankee will take advantage of Lucía.”

She wanted to make sure they understood her double-meaning. Not only could Zoila defend Lucía against foreigners, she could defend Lucía against them as well.

“And,” she continued, “I will make sure that her agent sends your entire family a little gift every few months.” She gestured as if she were handing out coins to all present, and all around the room doubting faces lit up with smiles.

“Really?” asked the old aunt.

“In fact, as soon as you allow me to pack Lucía’s suitcase and leave to arrange her papers, I will distribute the money the agent gave me to give to you, her loving family.” If Zoila had to bribe the family into behaving properly, then so be it.

This did the trick. The relatives cleared the room instantly, pacified by the prospect of receiving money simply because they were Lucía’s blood relations. None of them had bothered to make eye contact with Lucía, their little chaneque. Lucía herself sat impassively, her tiny head resting against a cold, hard wall. Looking at Lucía’s downcast posture and tragic gaze, Zoila found it impossible to reconcile this girl with the spitfire who entertained the throngs on the street corner with her effervescent dancing and crystal clear voice. Although Lucía was at the center of the conversations all around her, not one person—not even her mother— bothered to ask her what she thought about her pending journey.

For a moment, Zoila was tempted to reach out to Lucía, just to reassure her that everything would be fine as soon as the travel documents were in order. It was the sort of kind-hearted gesture that Felipe would have extended to a sad and confused girl—like the lonely girl Zoila used to be.

The pale yellow of Lucía’s skin reminded Zoila of vanilla orchids that bloom for only a few days and then quickly wilt on the vine. For the first time, with an impending sense of gloom, she realized that the turmoil of the voyage might be too much for little Lucía. Like a vanilla orchid, Lucía might wilt under the pressure of a new life in strange surroundings; she might not be able to perform, to meet the high expectations everyone imposed on her.

In that instant, Zoila decided to accelerate the pre-travel plans. She needed to get Lucía out of Veracruz. Lucía was as delicate as the spindly vanilla vines, but her entire family was trying to hang on her frail being, attempting to climb out of their poverty via her fragile dimensions. Zoila would not allow it. She pulled Señora Zárate into a quiet corner of the room.

“Why is it that you’ve just shown me the baptismal records for Manuel José and José de Jesus who were baptized at San Francisco de Asís Church,” Zoila asked in a hushed tone, so other people couldn’t hear. She pointed to the words on the document so the illiterate Señora Zárate knew what she was talking about. “And here are the records for Carlos Sebastian and for Irinea María, who were baptized in Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe Church in Paso de Ovejas. But where is Lucía’s record? When and where was Lucía baptized?”

“Uh, she was also baptized.” Señora Zárate was stalling. “You can take my word for it,”

“Señora, I need proof of Lucía’s birth. Actual proof.”

Señora Zárate shrugged. “Well, there she is. Isn’t that enough proof?”

“But what is her precise age and birth date?”

“It is exactly as my husband told the Yankee agent. Lucía was born in 1864 and she is twelve-years-old.” The Señora’s voice grew very shrill. “And she is still alive… unlike my tiny Manuelito.”

Señora Zárate started sobbing in such a loud way that Zoila couldn’t ask any more questions. There was a family secret, she could tell, that had to remain buried with the Zárate family. There was no point in probing any further: this would only delay her own departure from the port the following day. Lucía was her only ticket out of Veracruz, and Zoila had under twenty-four hours to gather all the correct documents if they were both to enter the United States. She couldn’t waste another minute trying to figure out why Señora Zárate wouldn’t give her Lucía’s birth or baptismal records. What she had to focus on now was complying with the Yankee agent’s orders.

The agent had disbursed a large sum of money to get Lucía on board the ship to the United States. If he was as cunning as any vanilla trader Zoila had ever known, he would only have done so knowing the potential return on his investment. She’d heard him refer to Lucía as his little mother lode, the place where the largest amount of gold can be found. As long as he made certain that his golden inve

stment arrived safely, Zoila would keep Señora Zárate’s secret about Lucía’s indeterminate age entombed.

Her father had taught her to strategize at many levels. In her current situation, he would have advised her to follow the money—“cherchez l’argent” —so she knew the most important step was to safeguard the money the Yankee had given her, and then to ask for more. The next step would be to secure the correct documents and to learn about Lucía’s health and food requirements. The following step, once they arrived in New Orleans, would be to get to know Lucía, to cheer and encourage her, and to guide her into becoming the most charming of human curiosities ever to be exhibited in the United States.

Within a few days of their arrival in New Orleans on May 27, 1876, the name of Lucía Zárate was on everyone’s lips. Tongues had not wagged this much since the famous Spanish opera singer Adelina Juana María Patti*— known as the Spanish Songbird—had visited a few years ago, performing at the French Opera House on Bourbon and Toulouse Streets. The crowds in New Orleans loved opera and they appreciated her lyric roles and crystalline voice, but it was Patti’s convoluted personal life of ex-husbands, jealous lovers, and financial ruin that really intrigued the locals. The throngs in New Orleans, like those mesmerized by Lucía in Veracruz, craved the role of bystanders at a calamity, almost as much as witnessing a unique miracle. The Spanish Songbird had satisfied their hankering for the misadventures of the famous, and now the mob wanted to be uplifted by the phenomenon of Lucía Zárate.

The diverse population of New Orleans always had a soft spot for any novelty arriving from the Hispanic world. Louisiana had been a part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain until 1802, so the fusion of cultures in this port city was as vibrant as that of Veracruz. Although some still argued over which came first, the beignet or the buñuelo, Tabasco or Louisiana hot sauce, most Creoles didn’t give a hoot about where there flavorful pleasures originated. They just wanted to enjoy life, to let the good times roll.

Lucía Zárate: The odyssey of the world’s smallest woman

Lucía Zárate: The odyssey of the world’s smallest woman Parisian Promises

Parisian Promises